Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JN0

Inglés UdeA - Cabezote - WCV(JSR 286)

Inglés UdeA - Cabezote - WCV(JSR 286)

Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JQ2

Signpost

Signpost

Generales

Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JQ1

Climate Variations: El Niño

Climate Variations: El Niño

Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JQ3

Portal U de A - Redes Sociales - WCV(JSR 286)

Portal U de A - Redes Sociales - WCV(JSR 286)

Z7_89C21A40L0SI60A65EKGKV1K57

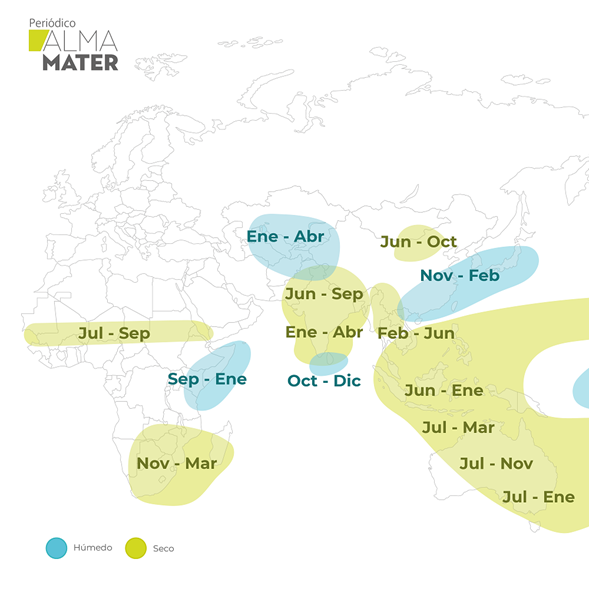

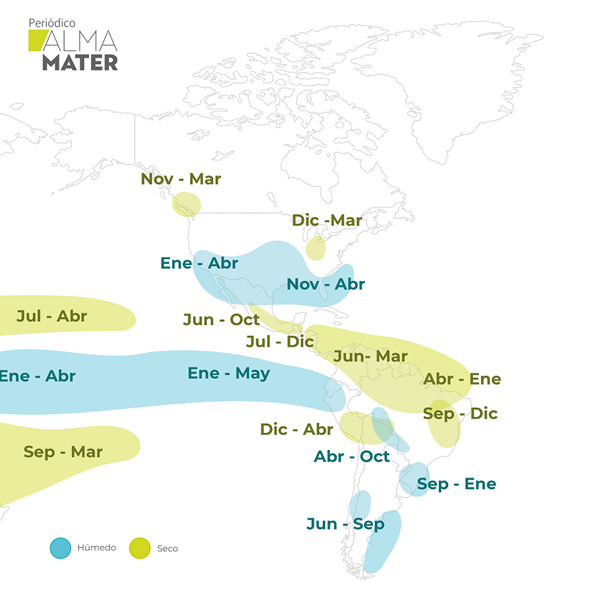

El Niño is a phenomenon of global scale, characterized by an increase in sea temperature in the central tropical Pacific and changes in winds in the tropical belt.

El Niño is a phenomenon of global scale, characterized by an increase in sea temperature in the central tropical Pacific and changes in winds in the tropical belt.