Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JN0

Inglés UdeA - Cabezote - WCV(JSR 286)

Inglés UdeA - Cabezote - WCV(JSR 286)

Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JQ2

Signpost

Signpost

Generales

Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JQ1

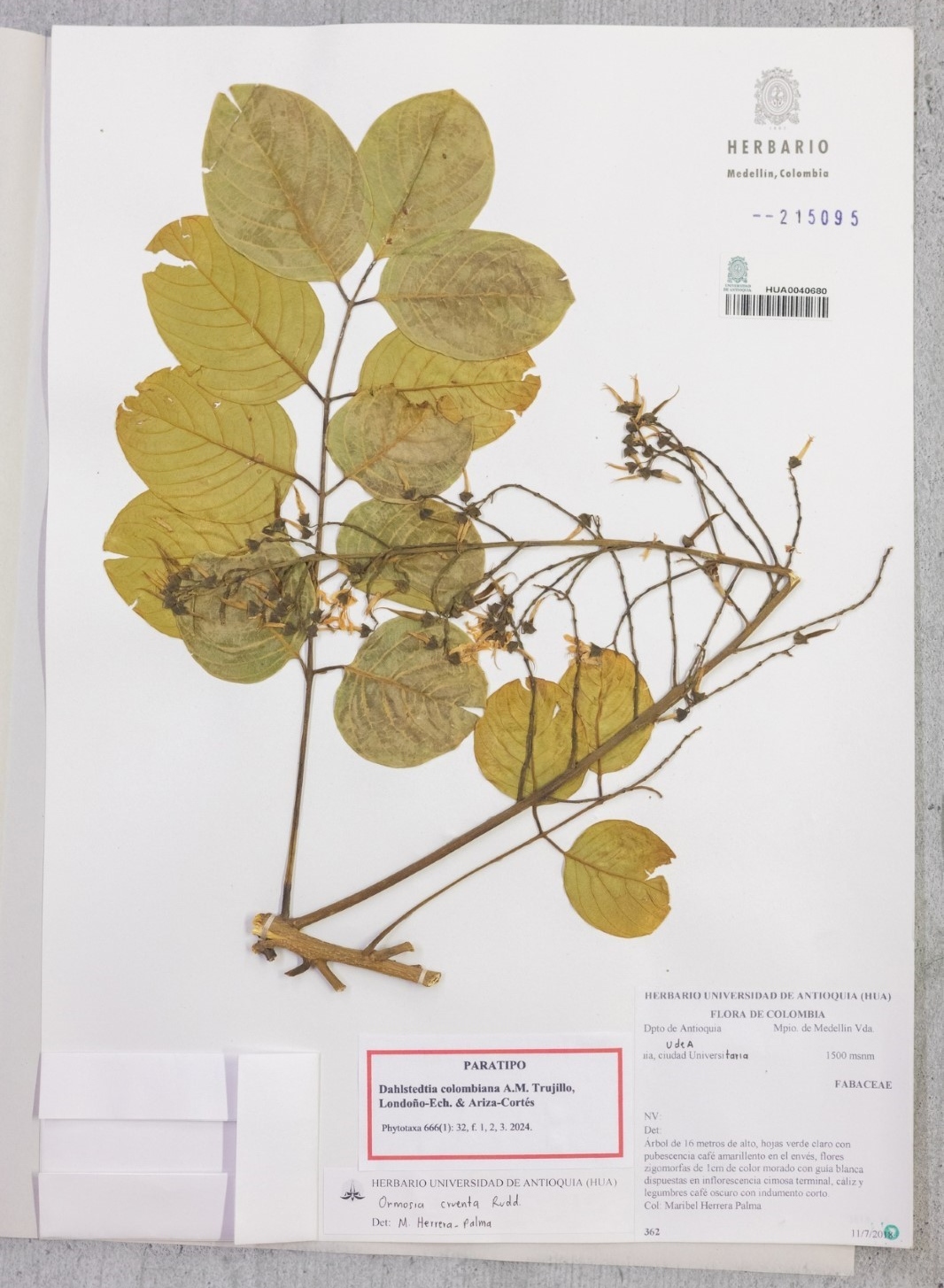

A new tree species was discovered at the UdeA Herbarium

A new tree species was discovered at the UdeA Herbarium

Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JQ3

Portal U de A - Redes Sociales - WCV(JSR 286)

Portal U de A - Redes Sociales - WCV(JSR 286)

Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3J60

Portal U de A - Listado Interna Sin Menu - WCV(JSR 286)

Portal U de A - Listado Interna Sin Menu - WCV(JSR 286)

1 resultado

Anterior | Siguiente

Z7_89C21A40L0SI60A65EKGKV1K57